By Benjamin George Coles

In May, Cyclone Fani displaced around 3.5 million people in Bangladesh and India. Even before that, around 10 million in Bangladesh had been evacuated due to climate emergencies in recent decades. Friendship works in places that are among the most vulnerable in the world to the effects of climate change, striving to help people survive and flourish.

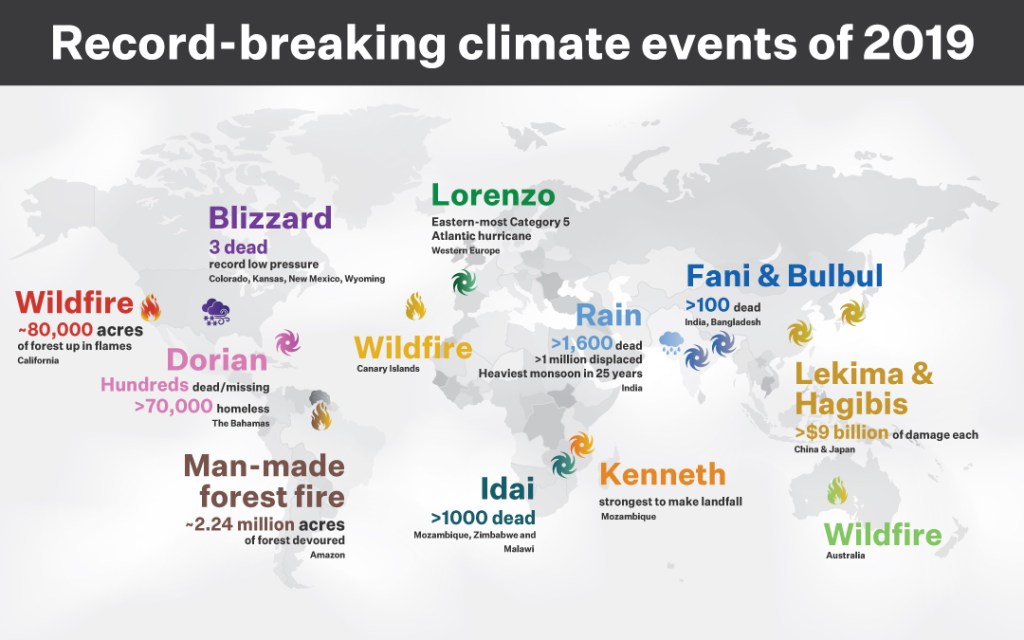

2019 has been an eventful year on the climate front, but it began relatively calmly. Then in early to mid-March, we had both that extraordinary blizzard that paralyzed the Midwestern United States, and Cyclone Idai tearing up Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Malawi. The latter became the deadliest and the most costly cyclone on record in the region, leaving over 1,000 dead and hundreds of thousands more in need of urgent help.

As if that weren’t bad enough, another cyclone, Kenneth, hit Mozambique only six weeks later, becoming the strongest to make landfall there since records began. This was also the first time the country had suffered two major cyclones in the same season.

Idai and Kenneth set the tone for what has been another terrible year of storms. The pick of the bunch was perhaps Hurricane Dorian, which struck The Bahamas in early September, leaving about 70,000 people homeless, and hundreds dead or missing. Prime Minister Hubert Minnis described it as the greatest crisis in the country’s history.

In monetary terms, though, Dorian was dwarfed by typhoons that hit China in August and Japan in October, which each caused damage worth over US$9 billion and were counted among the worst in the country’s history.

Aside from Fani, India and Bangladesh had Cyclone Bulbul just a few weeks ago. More than a hundred lives were lost in the two storms, but effective evacuation and disaster management measures, such as those organised by Friendship, saved many more. During Fani, the local government in Shyamnagar even co-opted Friendship staff to run its command centre.

Late September’s Hurricane Lorenzo spent most of its existence innocuously at sea, but, like many of the other record-breaking storms of the year, it demonstrated alarming changes in weather patterns. A Category 5 hurricane like Lorenzo bearing down on Western Europe was once unimaginable.

And the storms were just the start of it…

In early May, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services published its first report since 2005, warning of an accelerating rate of biodiversity loss and over a million species currently at risk of extinction. It emphasised that humans are largely to blame.

Then, after the hottest June on record, July became the hottest of all months on record. Unsurprisingly, an unprecedented rate of Arctic ice loss was recorded in the same period.

In August, citizens of Iceland held a funeral for Okjökull glacier, affectionately known as Ok, which a century ago covered more than 15 km2. Iceland’s Prime Minister unveiled a plaque inscribed with a letter to the future: “Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Also in August, India experienced the peak of its heaviest monsoon in 25 years. Floods there killed 1600 and displaced over a million people. Elsewhere in the world, Somalia, Kenya, the American Midwest and the Italian city of Venice have also all seen unprecedented flooding this year. In Bangladesh, flooding in some northern areas reached some of the highest levels on record. Again, Friendship’s work was instrumental in protecting the most vulnerable, with the raised plinths it has constructed serving as sanctuaries for whole communities.

Late August saw the biggest climate story of the year. Wildfires engulfed over 2.24 million acres of the Amazon rainforest, due to high temperatures and the long dry season, combined with the intentional slashing-and-burning of forest for agriculture and logging. Environmental groups and international leaders blamed Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s crude pro-business policies weakening environmental protections. Meanwhile Bolsonaro declined US$22 million in aid from the G7, saying that the problem was a domestic one. Fires were lighting up headlines throughout the second half of the year, with the Canary Islands, California and Australia also experiencing extreme wildfire seasons.

Then in November, air pollution reached record levels in large parts ofIndia, and Dhaka topped the list of cities with the worst air quality in the world for three days in a row.

In the same month, the United States formally began the process of pulling out of the Paris Agreement, in line with a decision made last year by President Trump, who has described climate change as a hoax invented by the Chinese to harm American businesses.

All this has provoked some strong responses. “You are failing us,” 16-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg told world leaders at the United Nations summit in September. “But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal.” Earlier, millions of young people all over the world had marched in a coordinated protest against climate inaction. A few days later Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau joined Greta at the helm of a 500,000-strong climate protest march in Montreal.

Is it a case oftoo little, too late? Two of the year’s most widely read essays – David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earthand Jonathan Franzen’sWhat if We Stopped Pretending?– suggest so. Taking that view, maybe the best news this year came in mid-September, when a team of astronomers at University College London announced they’d discovered for the first time water in the atmosphere of a planet orbiting within the habitable zone of a distant star.

Certainly it seems clear, from the year’s major news stories, that more and more people are going to be affected by the Climate Crisis in future, and Friendship’s work developing solutions for climate-impacted communities will be ever more vital.