Residents of char Kheyar Alga spend more than 20 days living on boats during Kurigram Flood

by Tahmeed Chaudhury

June 29, 2022

At the heart of the Brahmaputra River lies a char—a riverine sedimentary island—submerged to the point that when approaching from a distance, one could only see corrugated tin roofs sticking out of the water. Char Kheyar Alga, a low-lying island that emerged barely a couple of years ago, was one of the most affected, if not the most affected char during the Kurigram flood; the catastrophic flood in June that is still tormenting the northern parts of Bangladesh.

“Everyone here has been living on boats for 15 to 20 days,” said Jalal Sardar, an elderly resident of the char from the confines of his small boat. “High water levels and strong currents have washed many homes away. Some of us had to relocate our livestock to the mainland to prevent them from succumbing to the flood.”

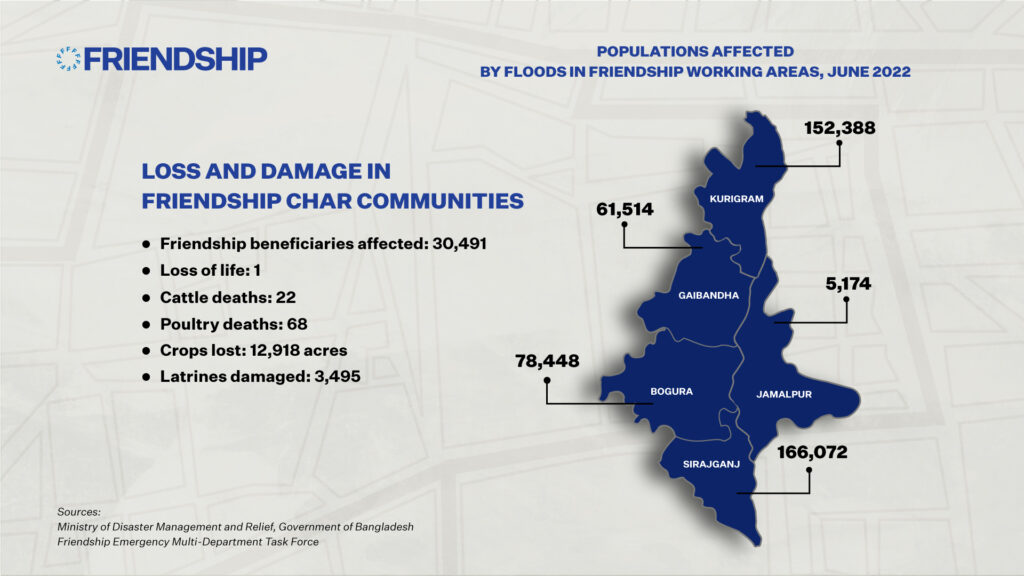

Heavy downpours combined with runoff from across the Indian border contributed to the worst flood in more than a decade this year in northeast Bangladesh, inundating villages and plaguing inhabitants with a shortage of food, scarcity of safe drinking water and poor hygiene. In the north, floodwaters seeped into the homes of char residents, forcing many into seeking shelter at nearby facilities or relatives’ houses on higher ground. Others stayed behind, with no other option than to accept their fates and wait for the ordeal to end.

While a number of chars bore the brunt of the disaster, Kheyar Alga was in a league of its own. With water levels elevating to almost five feet, residents had no means to stay indoors. Some could only watch as their belongings were washed away. They had to turn to boats as makeshift homes, until the water receded significantly.

Md. Abdur Rashid, 60, lived with his wife, three daughters and three grandchildren in a tin-shed home on a remote char in the middle of the Brahmaputra River. River erosion destroyed his home three times, the last of which saw the entire village consumed and hundreds of people displaced. “Floods took away everything we had. We had to start afresh after coming here three to four months ago,” he said.

These people, including Abdur Rashid, were only recently relocated to char Kheyar Alga after it emerged as a khaas (unclaimed) land in 2020. Friendship’s Inclusive Citizenship program, and the local district commissioner and Upazila Nirbahi Officer, arranged for land on the char to be handed over to them.

Md. Nazmul Hossain, project manager of Inclusive Citizenship in Kurigram, said, “After these people lost their lands to erosion in 2021, we inspected it with the local government and took measures to legally distribute it to the people.”

Only four months after moving to a new home, they found themselves in the midst of yet another crisis. Depending on farming and catching fish for a living, Md. Abdur Rashid, like many inhabitants in the locality, was without income and is fast running out of food stocks. “We eat one meal a day to save our remaining food,” he said.

During floods, poor sanitation and scarcity of safe drinking water pose a threat of diseases such as diarrhoea. “All the tube wells and latrines are under water. We are left with no choice than to boil river water for consumption. As for going to the bathroom, we row our boat to a secluded zone out of sight.”

Floods are an annual disaster in the river islands of the Brahmaputra. The flood season is yet to come this year, and even though the water is subsiding now, a bigger flood is likely in July or August.

Immersed homes, hunger and risk of diseases are not the only concerns of the inhabitants of char Kheyar Alga. Only months after they had found themselves a new home, they are now at risk of losing this one as well. Once floodwaters recede, there is a chance part of this land, if not all of it, will succumb to erosion. The floods pose an uphill test of resilience on a population that cannot seem to catch a break.