Derrière ce titre un brin incongru – car, bien entendu, les mangroves ne poussent pas à Luxembourg tout simplement parce qu’il n’y ni la mer ni le climat tropical – se cache pourtant une vérité. L’idée de ce vaste programme de reforestation des mangroves mis en place par Friendship au Bangladesh a germé depuis le Luxembourg et le projet a pu éclore grâce à des financements luxembourgeois. Voici l’histoire.

(English version below)

par Stéphane Van Haute

5 Octobre 2025

Retour en 2016. Patrick Losch, alors à la fois membre du Conseil d’Administration de Friendship Luxembourg, et président du Conseil d’Administration de la Fondation Hëllef fir d’Natur, visitait la région côtière du Bangladesh (sud-ouest, district de Satkhira) en compagnie de la fondatrice de Friendship Runa Khan. Connaissant sa passion pour les forêts, Runa lui avait demandé à maintes reprises s’il ne voyait pas des possibilités pour un projet forestier, ce qui ne faisait malheureusement pas de sens sur les îles à durée de vie limitée (les chars) du Brahmapoutre, région d’intervention historique de Friendship. Par contre, dans la baie du Bengale, en se déplaçant en bateau sur les fleuves Kholpetua et Kopothakho, Patrick a vu ce que d’autres ne verraient pas au premier abord : entre le fleuve et les minces digues d’argile se trouvent de larges pans de terre dénudés, soumis aux marées. Dans cet environnement côtier tropical, il se serait attendu à y trouver un écosystème de forêts de mangroves. Il faut en effet savoir que ces fleuves, largement inconnus et pourtant deux fois plus grands que la Moselle, se jettent dans le golfe du Bengale en passant par les Sundarbans, la plus grande forêt de mangroves du monde, patrimoine mondial de l’UNSECO, dont les deux tiers se trouvent au Bangladesh.

Lorsque l’on regarde une carte de la région, on peut supposer que, historiquement, les Sundarbans remontaient bien plus haut que la limite actuelle, probablement jusqu’à Shyamnagar et même au-delà, selon certains experts. Depuis l’époque coloniale, la pression croissante pour l’usage des terres, notamment pour la culture du riz et l’aquaculture, dans un pays très densément peuplé, a causé un recul des surfaces boisées. L’expansion humaine n’étant arrêtée que là où la salinité de l’eau des puits ne permettait plus la survie des colons. Heureusement, depuis une trentaine d’années, grâce l’inscription des Sundarbans au patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO et à une politique de conservation plutôt bien respectée malgré les difficultés auxquelles peut faire face un pays en développement, la limite entre les zones préservées (et interdites d’accès) et les zones habitées et cultivées semble stabilisée.

Au nord des Sundarbans, il existe effectivement de nombreuses surfaces non cultivées devant les digues où les mangroves devraient être encore présentes mais où elles ont quand-même disparu. L’autre élément frappant du paysage sont ces digues en terre qui s’érodent à chaque tempête et sont submergées en cas de cyclone, détruisant les habitations, les cultures et causant une catastrophe silencieuse en salinisant les sols.

Rapidement, Patrick a su démontrer à Runa l’intérêt d’un projet de reforestation des mangroves. Ils ont commencé sur le champ à rechercher la raison de l’absence d’arbres sur ces espaces et réfléchi à comment les y réintroduire. Ils ont interrogé les populations et autorités locales et il s’est avéré que, par nécessité, les très nombreux habitants y laissent paître leur bétail, empêchant ainsi toute régénération naturelle d’arbres. Il fallait donc impérativement impliquer les populations locales et leur trouver des alternatives de revenus. C’est en partant de ce constat qu’a émergé l’idée d’une Solution fondée sur la Nature et les populations locales [Community-led Nature-based Solution].

Fort de l’expérience en gestion d’écosystèmes qui est le cœur même de l’activité de la Fondation Hëllef fir d’Natur, Patrick a pu apporter un soutien conceptuel pour la partie nature et sylviculture en complétant ainsi la partie inclusion des communautés, point fort de Friendship Bangladesh, pour l’élaboration du projet. Les équipes de Friendship Bangladesh, aidées par un expert forestier local, ont ensuite étudié la faisabilité d’un tel projet en consultant les différentes parties prenantes. Parmi celles-ci, le Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD) a validé le concept qui s’inscrit dans les stratégies nationales et dans leur mandat de reforestation et de protection des mangroves. Une seconde visite exploratoire en juin 2017 a permis d’approfondir l’analyse des différentes options proposées par l’équipe sur place. Il est vite apparu évident que les mangroves pourraient aussi apporter de multiples avantages comparé aux solutions classiques, très coûteuses, pour la protection des digues.

À Dhaka, ils sont allés à l’ambassade des Pays-Bas consulter les experts néerlandais qui ont assisté le gouvernement bangladeshi pour l’élaboration du Delta Plan 2100 visant à assurer un delta sûr, résilient et prospère face aux enjeux climatiques. Ils y ont bien eu la confirmation qu’une solution fondée sur la nature était parfaitement appropriée et ont été encouragés à poursuivre l’idée de réintroduire les mangroves devant les digues. Non seulement les mangroves réduisent la force des vagues lors des tempêtes et évitent ainsi l’érosion des digues mais elles retiennent également les sédiments et stabilisent ainsi les accotements.

Il ne restait plus qu’à convaincre les autorités locales de donner les autorisations pour reboiser les terrains faisant partie du domaine public (ces fameuses vasières le long des fleuves), démarche pour laquelle l’intervention de Runa et des équipes de terrain de Friendship allait être décisive pour créer une relation de confiance. Enfin, l’implication des communautés locales a été déterminante pour définir les zones de plantation en fonction de leurs usages, pour établir un système de protection des jeunes arbres contre les chèvres, pour collecter des semences d’arbres (l’approche seeds-for-cash), pour créer des pépinières, planter les arbres et trouver des alternatives de revenu à l’élevage de chèvres.

Une fois le projet conçu et les autorités et populations convaincues, la suite de cette histoire revient à Luxembourg. Après la COP21 et l’Accord de Paris en 2015, le Ministère de l’Environnement, du Climat et de la Biodiversité (MECB) a développé sa stratégie de financement climatique international, alignée avec le « Paris Rulebook », manuel d’implémentation de l’Accord de Paris. Les fonds alloués à cette stratégie comprennent une enveloppe pour les ONG de développement, agréées par le Ministère de la Coopération. La nouveauté – et c’est important à signaler car assez unique en son genre – est que ces fonds sont additionnels. Comme le soulignait Care Danemark dans un rapport en 2023, « le Luxembourg est l’un des rares pays à garantir que les financements qu’il déclare à la CCNUCC s’ajoutent à son aide au développement. Son financement climatique international (FCI) a un budget indépendant et qui s’ajoute à son aide au développement ». En allouant une partie de ce budget à des ONG luxembourgeoises pour des projets d’adaptation climatique dans les pays du sud pour accroître leurs capacités face aux effets du dérèglement climatique, le MECB a adopté une approche pertinente. Il s‘agit d’utiliser les connaissances et les accès au terrain des ONG pour réaliser des projets qui mettent les communautés au centre et surtout, qui garantissent qu’une part très substantielle des fonds vont vers ceux qui en ont le plus besoin et sont en première ligne. Cela se distingue des grands financements internationaux dont l’argent est dilué au fur et à mesure des intermédiaires et dont finalement, seule une portion congrue, parfois seulement 10%, bénéficie aux plus vulnérables.

Dans ce mécanisme, le modèle sud-nord de Friendship a, là aussi, pu faire la différence. Friendship Luxembourg a pour objet d’appuyer, par des moyens financiers et techniques, des projets conçus et développés et au Bangladesh. À partir d’un coup de pouce initial du Luxembourg (l’appui technique de la Fondation Hëllef fir d’Natur) aux compétences bangladeshies, les équipes de terrain ont ensuite effectué l’analyse sociétale et culturelle appropriée afin de rendre l’idée réalisable et acceptable localement, et l’accès au financement a finalement été rendu possible parce que Friendship Luxembourg est agréée et éligible au mécanisme du MECB. Un exemple de complémentarité. La première demande de projet sur cinq années a pu être soumise au MECB fin 2017, aussi parce que Friendship Luxembourg avait renforcé son staff. Le projet a été validé le 21 mars 2018 et les premières plantations ont pu se faire en novembre 2018.

Après plus de 7 années, le résultat est saisissant. Le paysage est durablement transformé. L’impact est visible, tangible et largement perçu par les populations locales. Lors de la soumission de la première demande de financement, le MECB demandait si les avantages de l’augmentation de la résilience grâce aux mangroves seraient suffisamment motivants pour assurer la conservation des forêts. Il suffit d’écouter le témoignage de Molina Mondol, l’une des riveraines d’une zone reboisée, pour comprendre que oui. De plus, la biodiversité revient beaucoup plus vite qu’escompté initialement et on constate une accélération de la sédimentation et de la régénération naturelle de l’écosystème. Cela va même au-delà des mangroves puisque les riverains ont vu une augmentation de leur production agricole à l’intérieur des terres, désormais moins exposées à la salinisation.

La nomination au Prix Earthshot vient récompenser tout le travail réalisé depuis 2016. Cela permet de montrer que toutes les hypothèses initiales ont pu être validées : le modèle s’est avéré faisable et réaliste, il a un vrai focus climatique, il est cohérent, il répond aux besoins des bénéficiaires et aux priorités du pays, il y a des co-bénéfices liés aux ODD, il y a une vraie valeur ajoutée transformationnelle et un potentiel d’expansion. Et surtout, les mangroves protégées fournissent plus rapidement qu’escompté des revenus additionnels aux populations locales. Rien que la collecte de crabes, fruits et miel dépasse largement les maigres revenus qu’offraient les chèvres auparavant aux plus pauvres. Enfin, suite à une étude scientifique, nous savons que le projet a déjà séquestré plus 4.000 tonnes de carbone provenant de 15.000 tonnes de CO2.

La confiance et la prise de risque raisonnée dont a fait preuve le MECB en consentant au financement du reboisement des 100 premiers hectares ont été cruciaux pour tester le modèle et gagner de l’expérience. Après cette première phase pilote, le projet a pu s’étendre grâce à des donateurs privés, dont Banque Raiffeisen et ses clients dans le cadre de leur initiative de reforestation menée avec la Fondation Hëllef fir d’Natur. À travers leurs opérations bancaires journalières, les clients de Banque Raiffeisen contribuent à planter des arbres, au Luxembourg ou au Bangladesh, ce qui permet aussi de sensibiliser à la protection du climat et à la solidarité internationale.

Et tout cela n’est pas fini ! D’une part, le triple partenariat Banque Raiffeisen–Fondation Hëllef fir d’Natur–Friendship Luxembourg se poursuit. D’autre part, un nouveau projet de cinq ans financé par le MECB a démarré en juin 2025, avec de nouvelles activités pour répondre encore mieux aux besoins des communautés locales. Des contacts en cours entre Friendship et certains bailleurs internationaux laissent présager que dans les années à venir, le programme pourra connaitre une expansion considérable. Dans cette perspective, le fait que le premier projet pilote ait pu être réalisé grâce aux soutiens en provenance du Luxembourg prend d’autant plus d’envergure.

Dans l’histoire de ce programme unique réunissant autour d’un même objectif des partenaires multiples (ONG locales et internationales, État, entreprise), il faut aussi mentionner une nouvelle initiative qui a vu le jour en 2021 via Friendship Belgium : le Blue Mangrove Fund. Compte tenu de la capacité des mangroves à capter de grandes quantités de CO2, il s’agit de proposer un outil aux familles ou petites entreprises pour “compenser” leurs émissions de CO2 qu’elles ne sont pas en mesure d’éviter. Le principe est d’investir un montant permettant de reboiser une surface de mangroves qui va capter une quantité équivalente à ces émissions de CO2. C’est surtout une façon de participer activement aux efforts d’adaptation et d’atténuation climatique en contribuant à la création de puits carbone, avec tous les effets bénéfiques pour les populations locales et la biodiversité. Pour clore la boucle, l’initiative Blue Mangrove Fund revient à Luxembourg en 2022 et permet de rassembler de nouveaux donateurs autour du projet. Naturata, Elvinger, Hoss et Prussen, Innpact, Ripple Effect et une dizaine de familles font confiance au travail conjoint de l’équipe Friendship à Luxembourg et au Bangladesh. De cette manière, 35 hectares supplémentaires ont pu être reboisés.

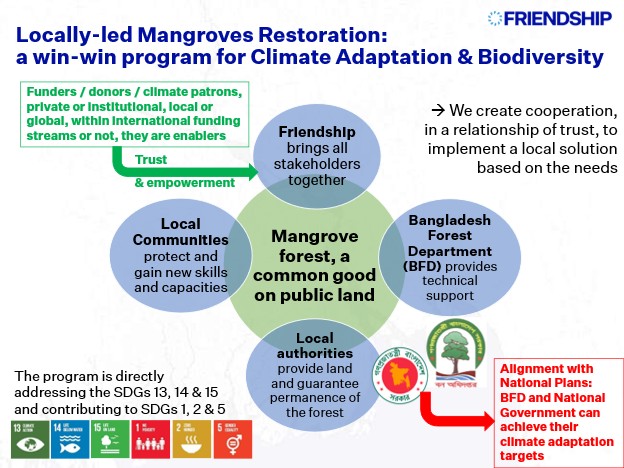

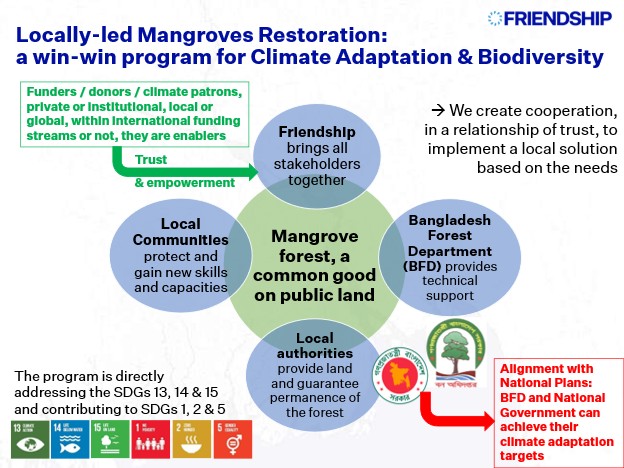

Pour conclure, on peut résumer ce programme suivant l’infographie ci-dessous. Grâce à la confiance et au soutien de partenaires multiples et variés, Friendship joue le rôle de facilitateur pour rassembler les communautés et les institutions locales (autorités et BFD) pour la gestion d’un bien commun, en ligne avec les ODD et les plans nationaux. C’est un modèle de coopération quadripartite d’une efficacité prouvée et extensible. On peut y voir la mise en pratique de ce qu’Elinor Ostrom, prix Nobel d’économie en 2009, a appelé des « arrangements institutionnels » pour assurer la gestion durable des biens communs. Lorsque l’information circule, lorsque toutes les parties prenantes coopèrent sur base de relations de confiance, les ressources naturelles peuvent être raisonnablement restaurées, utilisées et conservées. Dans les villages où Friendship travaille, les habitants ont intérêt à ce que la forêt revienne et ne soit plus détruite. Cette histoire et la nomination au Prix Earthshot ne montrent-ils pas que cet intérêt va au-delà de ces villages et est global, pour l’ensemble de l’humanité ?

Mangrove trees also grow from Luxembourg!

Behind this somewhat incongruous title – because, of course, mangroves do not grow in Luxembourg simply because there is no sea or tropical climate – lies a truth. The idea for this vast mangrove afforestation programme set up by Friendship in Bangladesh originated from Luxembourg, and the project was able to flourish thanks to Luxembourgish funding. Here is the story.

by Stéphane Van Haute

5 October 2025

Back in 2016, Patrick Losch, then a member of the Board of Directors of Friendship Luxembourg and Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Hëllef fir d’Natur Foundation, was visiting the coastal region of Bangladesh (south-west, Satkhira district) with Friendship founder Runa Khan. Knowing his passion for forests, Runa had asked him repeatedly if he saw any possibilities for a forestry project, which unfortunately did not make sense on the short-lived islands (chars) of the Brahmaputra, Friendship’s historic area of operation. However, in the Bay of Bengal, travelling by boat on the Kholpetua and Kopothakho rivers, Patrick saw what others would not see at first glance: between the river and the thin clay embankments are large areas of bare land, subject to the tides. In this tropical coastal environment, he would have expected to find a mangrove ecosystem. It is important to note that these rivers, largely unknown and yet twice as large as the Moselle, flow into the Bay of Bengal via the Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, two-thirds of which is located in Bangladesh.

When looking at a map of the region, one can assume that, historically, the Sundarbans extended much further than the current boundary, probably as far as Shyamnagar and even beyond, according to some experts. Since colonial times, growing pressure for land use, particularly for rice cultivation and aquaculture, in a densely populated country, has caused a decline in forest cover. Human expansion was only halted where the salinity of the water in the wells made it impossible for settlers to survive. Fortunately, over the past 30 years, thanks to the Sundarbans’ designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a conservation policy that has been fairly well respected despite the difficulties faced by a developing country, the boundary between preserved (and off-limits) areas and inhabited and cultivated areas seems to have stabilised.

In the north of the Sundarbans, there are indeed many uncultivated areas in front of the embankments where mangroves should still be present but have nevertheless disappeared. Another striking feature of the landscape are these earthen embankments, which erode with every storm and are submerged during cyclones, destroying homes and crops and causing a silent disaster by salinising the soil.

Patrick quickly demonstrated to Runa the benefits of a mangrove reforestation project. They immediately began investigating why there were no trees in these areas and considered how to reintroduce them. They interviewed local residents and authorities and discovered that, out of necessity, the large number of inhabitants let their livestock graze there, preventing any natural regeneration of trees. It was therefore essential to involve the local population and find alternative sources of income for them. This observation led to the idea of a Community-led Nature-based Solution.

Thanks to an extensive experience in ecosystem management, which is at the heart of the Hëllef fir d’Natur Foundation’s activities, Patrick was able to provide conceptual support for the nature and forestry aspects of the project, complementing Friendship Bangladesh’s strength in community inclusion. The Friendship Bangladesh teams, assisted by a local forestry expert, then studied the feasibility of such a project by consulting with the various stakeholders. Among these, the Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD) validated the concept, which is in line with national strategies and their mandate for reforestation and mangrove protection. A second exploratory visit in June 2017 was an opportunity to further analyse the various options proposed. It quickly became clear that mangroves could also offer multiple advantages over traditional, very costly solutions for protecting embankments.

Back in Dhaka, they visited the Dutch Embassy to consult with Dutch experts who assisted the Bangladeshi government in developing Delta Plan 2100, which aims to ensure a safe, resilient and prosperous delta in the face of climate challenges. They received confirmation that a nature-based solution was perfectly appropriate and were encouraged to pursue the idea of reintroducing mangroves in front of the embankments. Not only do mangroves reduce the force of waves during storms, thereby preventing erosion of the embankments, they also retain sediment and thus stabilise those embankments.

All that remained was to convince the local authorities to grant permission to reforest public land (the mudflats along the rivers), a process in which Runa and Friendship’s field teams played a decisive role in building trust. Finally, the involvement of local communities was crucial in defining planting areas according to their uses, establishing a system to protect young trees from goats, collecting tree seeds (the seeds-for-cash approach), creating nurseries, planting trees and finding alternative sources of income to goat farming.

Once the project has been designed and the authorities and populations convinced, the rest of the story returns to Luxembourg. Following COP21 and the Paris Agreement in 2015, the Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Biodiversity (MECB) developed its international climate finance strategy, aligned with the Paris Rulebook, the implementation manual for the Paris Agreement. The funds allocated to this strategy include a budget for development NGOs accredited by the Ministry of Cooperation. What is new – and important to note because it is quite unique – is that these funds are additional. As Care Denmark pointed out in a 2023 report, “Luxembourg is one of the few countries who ensure the finance they report to the UNFCCC is additional to their support for development. Its International Climate Finance (ICF) is independent and on top of its development support.” By allocating part of this budget to Luxembourg NGOs for climate adaptation projects in southern countries to increase their capacity to cope with the effects of climate change, the MECB has adopted a relevant approach. The aim is to use the NGOs’ knowledge and access to the field to carry out projects that put communities at the centre and, above all, ensure that a very substantial proportion of the funds go to those who need them most and are on the front line. This differs from large-scale international funding, where money is diluted as it passes through intermediaries and, in the end, only a small portion, sometimes as little as 10%, benefits the most vulnerable.

In this mechanism, Friendship’s South-North model has also made a difference. Friendship Luxembourg aims to provide financial and technical support for projects designed and developed in Bangladesh. Following the initial support from Luxembourg (technical support from the Hëllef fir d’Natur Foundation) to Bangladeshi expertise, teams on the ground then carried out the appropriate social and cultural analysis to make the idea feasible and acceptable locally, and access to funding was ultimately made possible because Friendship Luxembourg is accredited and eligible for the MECB funding. An example of complementarity. The first five-year project application was submitted to the MECB at the end of 2017, also because Friendship Luxembourg had strengthened its staff. The project was approved on 21 March 2018 and the first plantings took place in November 2018.

After more than seven years, the results are striking. The landscape has been permanently transformed. The impact is visible, tangible and widely perceived by local communities. When the first funding application was submitted, the MECB asked whether the benefits of increased resilience thanks to mangroves would be sufficient motivation to ensure forest conservation. One need only listen to the testimony of Molina Mondol, a resident of a reforested area, to understand that the answer is yes. In addition, biodiversity is returning much faster than initially expected, and there has been an acceleration in sedimentation and natural regeneration of the ecosystem. This goes beyond mangroves, as residents have seen an increase in their agricultural production inland, which is now less exposed to salinisation.

The Earthshot Prize nomination recognises all the work carried out since 2016. It demonstrates that all the initial assumptions have been validated: the model has proven to be feasible and realistic, it has a real climate focus, it is consistent, it meets the needs of beneficiaries and the country’s priorities, there are co-benefits linked to the SDGs, there is real transformational added value and potential for expansion. Above all, the protected mangroves are providing additional income to local populations faster than expected. Crab, fruit and honey harvesting alone far exceeds the meagre income that goats previously provided to the poorest. Finally, following a scientific study, we know that the project has already sequestered more than 4,000 tonnes of carbon from 15,000 tonnes of CO2.

The trust and calculated risk-taking showed by the MECB in agreeing to finance the reforestation of the first 100 hectares were crucial in testing the model and gaining experience. After this initial pilot phase, the project was able to expand thanks to private donors, including Banque Raiffeisen and its customers as part of their reforestation initiative with Foundation Hëllef fir d’Natur. Through their daily banking transactions, Banque Raiffeisen’s customers contribute to planting trees in Luxembourg or Bangladesh, which also raises awareness of climate protection and international solidarity.

And that’s not all! On the one hand, the triple partnership between Banque Raiffeisen, Foundation Hëllef fir d’Natur and Friendship Luxembourg is continuing. On the other hand, a new five-year project funded by the MECB was launched in June 2025, with new activities to better meet the needs of local communities. Ongoing contacts between Friendship and certain international donors suggest that the programme could expand considerably in the coming years. In this context, the fact that the first pilot project was made possible thanks to support from Luxembourg takes on even greater significance.

In the history of this unique programme, which brings together multiple partners (local and international NGOs, government, businesses) around a common goal, it is also worth mentioning a new initiative launched in 2021 via Friendship Belgium: the Blue Mangrove Fund. Given the ability of mangroves to capture large amounts of CO2, the aim is to offer families and small businesses a tool to “offset” their CO2 emissions that they are unable to avoid. The principle is to invest an amount that will enable the reforestation of an area of mangroves that will capture an equivalent amount to these CO2 emissions. Above all, it is a way of actively participating in climate adaptation and mitigation efforts by contributing to the creation of carbon sinks, with all the benefits this has for local populations and biodiversity. To close the loop, the Blue Mangrove Fund initiative returned to Luxembourg in 2022, bringing new donors on board for the project. Naturata, Elvinger, Hoss and Prussen, Innpact, Ripple Effect and a dozen families have placed their trust in the joint work of the Friendship team in Luxembourg and Bangladesh. As a result, an additional 35 hectares have been reforested.

To conclude, this programme can be summarised as shown in the infographic below. Thanks to the trust and support of multiple and varied partners, Friendship acts as a facilitator to bring together local communities and institutions (authorities and BFD) for the management of a common good, in line with the SDGs and national plans. It is a model of quadripartite cooperation with proven and scalable effectiveness. It can be seen as the practical application of what Elinor Ostrom, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics, called “institutional arrangements” to ensure the sustainable management of common goods. When information flows and all stakeholders cooperate on the basis of trust, natural resources can be reasonably restored, used and conserved. In the villages where Friendship works, the inhabitants have an interest in seeing the forest return and no longer be destroyed. Do this story and the Earthshot Prize nomination not show that this interest goes beyond these villages and is global, for the whole of humanity?