by RAEED ABD-ALLAH CHOWDHURY

September 29, 2021

Amidst the intermittent lockdowns, multiple waves of covid-19 infections, logistical issues and significant threat to personal health, Mohammad Ahasan Habib, project officer, Inclusive Citizenship at Gaibandha helped 163 people to register online for their vaccinations. Most of them are day-labourers, owners of small tea-stalls or grocery shops, or women who are working as domestic helpers in the remote northern district of Gaibandha. None of them had the internet connections necessary to complete the online registration process.

“I remember one middle aged woman, must have been about 50 years old,” says Ahasan. “She kept telling me to come to her village, so finally I managed to find time to go all the way there, to Moddho Uriya. I signed her up, sitting on the bank of the Jamuna, taking in the sights, and before I knew it, she’d brought so many others I lost count. Let’s just say I had to use three phones other than my own because they all ran out of battery charge or data,” says Ahasan.

The Covid-19 pandemic is now in its 19th month in Bangladesh, a small, overpopulated, developing country. The social, economic, financial and public health issues caused by the virus, as well as the logistical hurdles in handling it, are immense. Resources and manpower are heavily limited, but the demands are high. A good portion of the 170 million citizens lives in some of the most remote, climate-affected areas in the world.

These communities have little by way of infrastructure or access to a stable internet connection required for registration. Many still lack the formal identification, and the means to access or collect it. Literally, these communities have no means of signing up for the vaccine.

Friendship has been working to assist remote communities to register and print vaccination cards, using this extant network and trust within the community. The process was started from 27 July and so far the paralegals have assisted almost 3,552 char dwellers to register for covid vaccination. Currently, over 2,000 have received vaccinations.

23 Friendship paralegals out of 80 were provided with smartphones in May this year to input their daily service updates online, which are then monitored real time. In addition to their usual services, they also helped people with no access to the system register for their vaccinations.

With the possibility of the pandemic persisting for years, Friendship is trying to explore new avenues of monitoring the vaccination rollout through the introduction of an online database. Given that physical monitoring has become unviable during the most challenging circumstances due to lockdowns, this arrangement should prove more effective, states Mahbubur Rahman Bhuiyan, a manager at Friendship’s Inclusive Citizenship.

“The local government has been very enthusiastic and encouraging about our help,” says Ahasan, “and they’ve offered to assist in any way possible. We’ve always worked together, since long before the pandemic, so we have a long-standing good relationship. Everything we’ve been doing about handling the pandemic has been in cooperation with them.”

“I realised how overwhelming it must be, trying to get vaccines to everyone in the country, especially in these really remote areas,” continues Ahasan. “There was a mass-vaccination drive recently, but that wasn’t nearly enough. We need to go door-to-door to make sure everyone knows what to do, and we help them to do it. I’ve personally registered people at tea-stalls, at the market, sitting by the riverside—wherever I met someone who hadn’t registered yet.”

The government has declared that from August 7 people can get their vaccination without registration, showing the National Identification (NID) cards at the union administrative level during their mass-vaccination campaign. Both the Civil Surgeon offices of Gaibandha and Kurigram districts have requested Friendship to continue the paralegal registration process, due to the logistical issues. Both the Civil Surgeons have given Friendship written approval for running the registration process. A handful of upazilla (sub-district) hospitals have received stocks of vaccines, and so that is where these communities are directed.

“The upazila administrative offices are readily using the paralegals help to spread the word,” says Ahasan.

That is a necessary measure, as the people of Shariakandi, in Bogura district are hesitant to sign up for or take vaccinations, reports the Prothom Alo news media. They’ve been prey to rumours and misinformation that the vaccine is dangerous, and causes severe side effects, including death.

Volunteers and staff have been going door-to-door to convince them otherwise, and have had their work cut out for them already, with the logistical issues stemming from the lockdowns. Despite that, camps have been set up for the government’s mass-vaccination drive and the local communities have been encouraged to come by. Friendship paramedics were asked to deliver jabs at one vaccination centre in Shariakandi to administer the vaccines at the behest of the local authorities. On the first day on August 7, Friendship medical staff administered 377 vaccination shots, and since then a further 490 in a second camp in September.

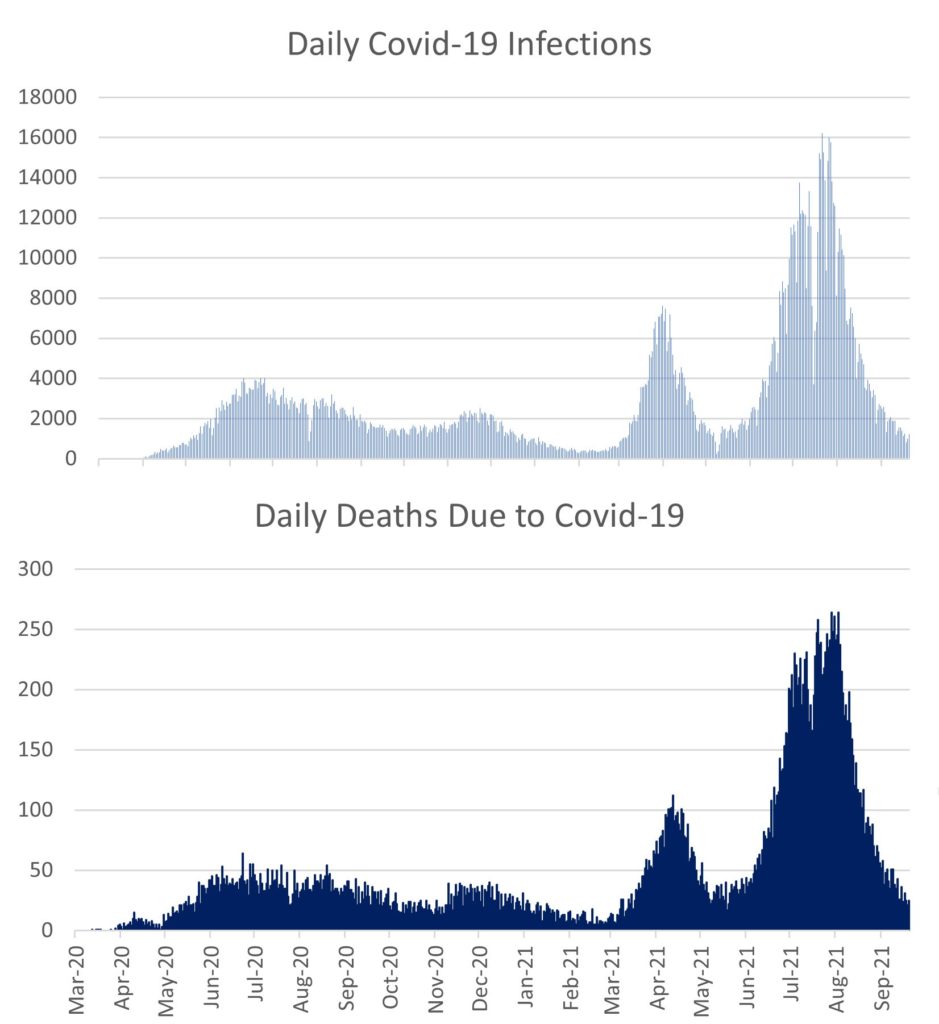

The official number of Covid-19 infections in Bangladesh is on a clear downward trajectory, with 1,310 new cases and 31 deaths registered yesterday. The number of cases and deaths peaked at 16,230 and 230 respectively two months back. Out of a population of 160 million, 14 million have received their second doses so far. With schools and university campuses opening this month, the challenge for Bangladesh will be to quickly vaccinate most of its adult population.